During its campaign to influence the 2016 American election, the Internet Research Agency operated out of a building on Savushkina Street in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo: Miles McCain

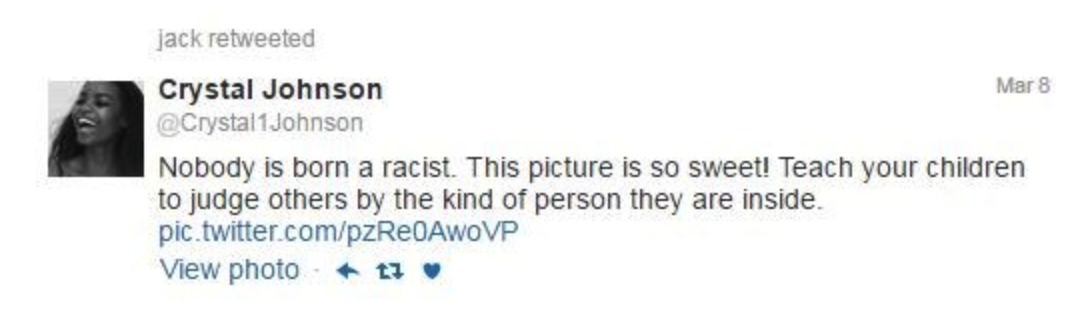

During its campaign to influence the 2016 American election, the Internet Research Agency operated out of a building on Savushkina Street in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photo: Miles McCainOn March 8, 2016, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey retweeted @Crystal1Johnson, a Twitter account that appeared to be run by a black American woman. The tweet itself was benign: “Nobody is born a racist. This picture is so sweet! Teach your children to judge others by the kind of person they are inside.” Unbeknownst to Dorsey, however, the account he retweeted did not belong to Crystal Johnson—instead, it belonged to the Internet Research Agency, a Russian state-sponsored organization more popularly known as the “Russian troll factory.”

Twitter CEO @jack retweeted @Crystal1Johnson, a confirmed IRA account. Photo: NBC News

Twitter CEO @jack retweeted @Crystal1Johnson, a confirmed IRA account. Photo: NBC NewsDorsey was far from the only person fooled by the trolls. On January 29, 2018, Twitter notified 1.4 million users that they had interacted with Russian trolls by following, retweeting, quoting, replying to, mentioning, or liking an IRA-linked account. Among the users notified were President Donald Trump, the Washington Post, Richard Spencer, Nicki Minaj, BuzzFeed, NBC News, Anthony Scaramucci, Sean Spicer, and Sen. Ted Cruz.

The IRA’s disinformation campaign did not limit itself to Twitter: on October 30th 2017, Facebook admitted that the IRA reached 126 million Facebook users by operating fake accounts and pages. That same day, Google revealed that it had served ads during the 2016 election cycle linked to the Russian government.

The IRA didn’t buy its way into American public discourse—instead, the infiltration came organically. While the IRA did buy ads to promote its content on Facebook, for example, these sponsored messages only reached 10 million users—less than one-tenth of the 126 million total Facebook users who were exposed to IRA propaganda. Indeed, the vast majority of impressions did not come as a result of advertising: on Twitter, IRA troll Tweets constituted a startling 0.74% of election-related content.

On October 31st 2017, the Senate Judiciary subcommittee on crime and terrorism questioned representatives from Twitter, Facebook, and Google about the scope and scale of Russian meddling on their platforms. Over several days of testimony, the companies disclosed what they knew about the meddling on their platforms. But when lawmakers asked whether the companies were confident they had unearthed the full scope of the Russian meddling campaign on their platforms, representatives from Facebook and Twitter answered “No.”

As the representatives acknowledged, much remained—and remains—unknown about the Russian effort to use social media to influence the 2016 American election. We do know, however, that the disinformation campaign respected no boundaries: it promoted both conservative and liberal messaging, reached nearly a majority of Americans, and incited distrust in the American political system.

The Russian government saw the power of social media as a tool to influence American civil discourse, and seized on the opportunity to weaponize it. To this end, we speculate that Russia had three distinct—but closely related—objectives in its disinformation campaign leading up to the 2016 election: to incite division, generate distrust, and influence elections.

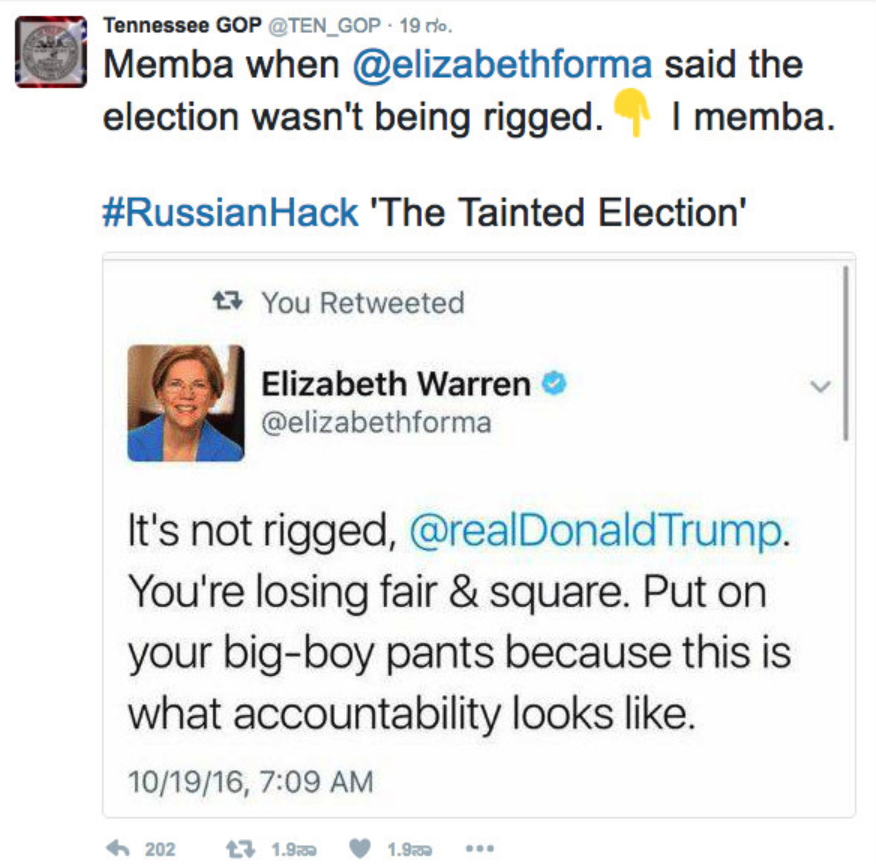

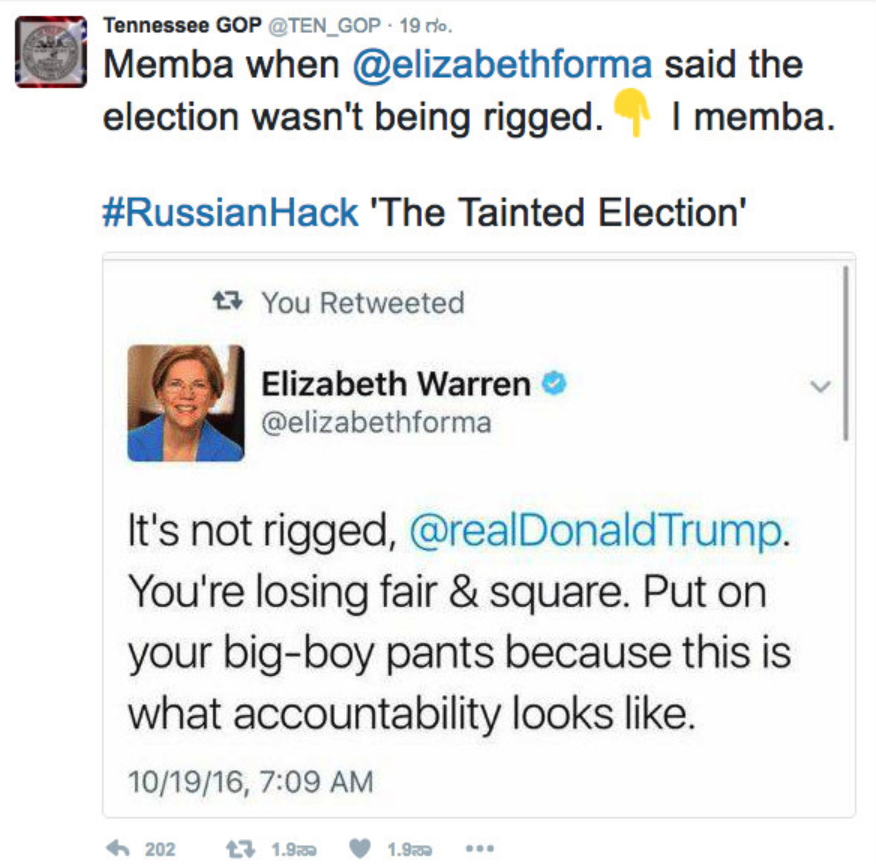

The IRA impersonated the Tennessee Republican Party on Twitter using the handle @TEN_GOP. Photo: Vox

The IRA impersonated the Tennessee Republican Party on Twitter using the handle @TEN_GOP. Photo: VoxThe IRA, posing as both left wing groups (Black Lives Matter, for example) and right wing groups (promoting mainstream conservative issues such as gun rights, hard-line immigration policies, and anti-Clinton rhetoric) inflamed racial and partisan tensions. Importantly, the trolls exploited existing divisions within the United States and promoted a spectrum of content designed to amplify these divisions.

The IRA impersonated the Tennessee Republican Party on Twitter using the handle @TEN_GOP. Photo: Vox

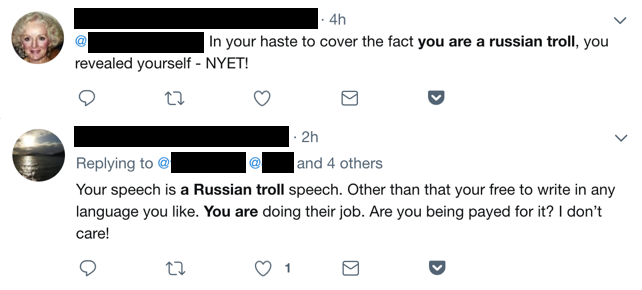

The IRA impersonated the Tennessee Republican Party on Twitter using the handle @TEN_GOP. Photo: VoxIRA trolls also actively sought to spread falsified information with the intent of discrediting people and movements they opposed. Common targets of the IRA included President Obama, undocumented immigrants, and high-level Republicans such as Sen. John McCain, who the IRA degraded in factually-incorrect posts and memes. (One post, for example, insinuated that Obama was connected to the Muslim Brotherhood.) This content was widely shared, and served to bolster support for Trump and delegitimize his opponents. More insidious, however, was the opportunity that Russian trolls provided: they allowed organic online movements to be discredited as “Russian trolls,” just as the fake news epidemic provided an opportunity for Trump to discredit the mainstream American media.

The existence of Russian trolls allows Twitter users to discredit one another as foreign sockpuppets. Photo: Twitter

The existence of Russian trolls allows Twitter users to discredit one another as foreign sockpuppets. Photo: TwitterA primary objective of the Russian disinformation campaign was to influence electoral outcomes in favor of Republicans—specifically, to spur conservatives to vote in key swing elections, divert Democratic voters towards Jill Stein, and suppress the African-American vote. Aided in large part by the ability to target specific demographics on social media and the viral tendencies of fringe political content, the IRA was extremely effective at spreading its messaging. Trolls posing as black activists created Instagram accounts with names such as “Woke Black” and “Blacktivist” to dissuade African-Americans from voting for Hillary Clinton. These accounts distributed memes and images highlighting, for example, Clinton’s insensitive use of the term “super-predator” in reference to young Black men in 1996.

The Russian operation indicated a high degree of sophistication and cultural understanding in its efforts to influence the American public. IRA-backed accounts often spread political messaging in the form of highly-shareable memes, which were often virtually indistinguishable from organic American content.

On a message board for the trolls, one post suggested that if “you write posts in a liberal group … you must not use Breitbart titles” and “if you write posts in a conservative group, do not use Washington Post or BuzzFeed’s titles.” To target liberal audiences, trolls were instructed to post in the morning—night in America—as “L.G.B.T. groups are often active at night” and to target conservatives, they would post “just before [the conservatives] left work for the day. And while these instructions were often grounded in deeply offensive stereotypes—one troll suggested keeping posts simple when aimed at queer people of color, explaining that “colored L.G.B.T. are less sophisticated than white”—they nonetheless indicate a formidable awareness of U.S. culture.

Russia’s disinformation campaign is far from over. Using similar tactics to those employed in 2016, IRA trolls continue to spread false and divisive propaganda across social media in an attempt to influence the 2018 midterm elections and American democracy more broadly. A key development in recent disinformation efforts, however, is the shift to incite offline activity in addition to online activity.

IRA accounts, such as "Resisters", promoted real-world rallies to incite division and violence. Photo: Facebook via the Washington Post

IRA accounts, such as "Resisters", promoted real-world rallies to incite division and violence. Photo: Facebook via the Washington PostAs part of their new campaign, IRA accounts promoted and set up events on social media, including a counterprotest to a white nationalist rally. Though these events are often created by legitimate American political organizations, their co-option by Russia indicates a desire to sow chaos both on- and offline.

IRA accounts, such as "Resisters", promoted real-world rallies to incite division and violence. Photo: Facebook via the Washington Post

IRA accounts, such as "Resisters", promoted real-world rallies to incite division and violence. Photo: Facebook via the Washington PostAnother equally alarming result of Russia’s Internet meddling—both in 2016 and now—is the rise of domestic disinformation. According to Molly McKew, a researcher at New Media Frontier, “there are now well-developed networks of Americans targeting other Americans with purposefully designed manipulations,” many of which are modelled—intentionally or not—after Russian efforts.

The lasting legacy of Russia’s 2016 disinformation campaign and its present-day efforts to influence the 2018 midterm elections are difficult to quantify. Some argue that the Russian efforts were ineffective in swaying elections; others argue the opposite. Regardless, its secondary effects—distrust in American media and politics, the prevalence of disinformation, and deeper partisan and racial divisions—will only serve to erode our democratic institutions if they continue unchecked.

We believe a modest but necessary step forward in combatting Russian disinformation efforts is to spread awareness of the Russian disinformation campaign and make the truth—what really happened—accessible to a wide variety of audiences.

As part of our inquiry into the Russian disinformation campaign, we seek to do just that. Join us as we identify trends in IRA content by developing a machine learning model to identify Tweets similar to known Russian propaganda. The effect, we hope, will be to make the world of Russian disinformation ever so slightly more understandable.